The identification and analysis of collocations – statistically significant bonds and frequent pairings of words in a corpus or sample – can be used to obtain insight into conceptual relationships and terminological associations. Some of the salient collocations can be quite novel or ideologically charged, which can allow us to notice patterns that would be rarely captured in linear processing (Kennedy, Brooks & Cherniaeva, 2024). In addition, collocational prosodies of stretches of discourse, for example when certain nouns consistently collocate with evaluative or emotional modifiers, can shed light on discursive strategies of legitimization, personalization or polarization.

This is arguably the case in the Polish-language subcorpus of tabloid war coverage that I have been working on for the study I presented at the 29th Conference of the International Association of Intercultural Communication Studies (IAICS) in September 2024.

Presentations from the IAICS conference to be found in CORECON “results” page

How do tabloids represent social reality through content and style?

According to the literature about tabloids, news presentation there is often juxtaposed with the so-called “broadsheet” or quality journalism, especially regarding the obliteration of the separation of “fact” from “opinion” (Bingham & Conboy, 2015). In fact, most journalism relies on value judgments at any stage of news production: from news gathering, to news selection, writing, editing and presenting. However, unlike broadsheet reports that tend to withhold judgments, tabloids make stronger evaluations and verbalize competing truth claims in order to resolve the controversy, rather than leave the audience to evaluate the facts on their own (Molek-Kozakowska, 2013). They often do this with reference to basic emotions and a rather conservative sense of morals. In addition, tabloids tend to refer to alternative or celebrity sources, rather than only to institutional actors, in which they project a sense of commonsensical “truthiness” of the coverage (Zelizer, 2009).

In the first stage of the study I filtered and analyzed the purposive comparative dataset of 568 texts harvested from the online versions of two popular English-language tabloids, The Mirror (UK) and The New York Post (US), and two top Polish-language outlets, SuperExpress and Fakt. I wanted to look at the degree of agency of represented social actors and the schematic storylines they are involved in. I used transitivity analysis and social actor analysis of headlines related to the war in Ukraine in each outlet to map how tabloids simplify complex issues and engage audiences.

In my tabloid headline dataset I have been able to see that personalization of conflict is evident particularly in the headlines where the warring leaders – Vladimir Putin and Volodymyr Zelensky – are individualized and named. The outcome is a human-centric construction of a war storyline, as if it was between Putin primarily attacking Ukraine and (to a lesser degree) Zelensky defending it, by what he says to international leaders and the Ukrainian nation (Wilk & Molek-Kozakowska, 2024). Obviously, the clashing armies are principal actors too, tied in a fight between evil and good, and fiercely defending specific territories, spaces and their inhabitants.

How do tabloid collocations reveal discursive strategies?

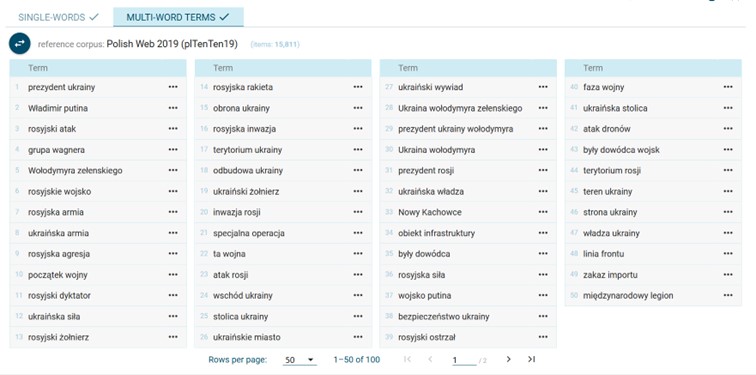

The above insights about personalization, moralization, polarization and additional spatialization have been confirmed with the aid of a larger quantitative analysis of the Polish subcorpus of tabloid materials (headlines, leads and copy of 300 texts from the Polish-language part of the dataset). With the use of Sketch Engine’s “Multi-word terms” statistical analysis, it was possible to identify 50 strongest collocations whose keyness and saliency was established against the backdrop of a reference corpus of Polish Web 2019 (plTenTen19).

The strategy of personalization in tabloid war coverage is evident. Some of the top strongest collocations refer to belligerent leaders, namely: “Ukraine president” (1, 29 – the smaller the number, the stronger the relation between the words), “Vladimir Putin” (2), “Volodymyr Zelensky” (5, 28, 30), “Russian dictator” (11), “Russia president” (31).

Needless to say, in tabloids Russians and Ukrainians are represented as attackers/villains and defenders/victims, respectively. When it comes to the identification of the Russian side of the conflict, the most salient collocations of “Russian” involve military participants on the side of the aggressor: troops (6, 37), army (7), soldiers (13) and rockets (14). Certain abstract processes are also evident in the ways the Russian actions are labelled with the negative moral evaluation implied, mainly as “attacks” (3, 23), “aggression” (9), “invasion” (16, 20) and “shelling” (39). It is clear that these terms attribute responsibility for war to Russians, additionally connoting brutality and criminality. Strong collocates of the adjective “Ukrainian” include abstract or neutral military terminology, such as: “army” (8), “force” (12), “defense” (15), “soldier(s)” (19), “intelligence” (27), “authorities” (32, 47), and “security” (38). This contributes to the polarized image of the war: all Russians end up to be evil attackers and all Ukrainians are shown as brave fighters. This may lead to a dangerous overgeneralization.

However, there are also strong collocates between the adjective “Ukrainian” and spatial denotation, namely: “territory” (17), “east” (24), “capital” (25, 41), “city” (26), or “area” (45). The emphasis in the coverage of Ukraine war thus seems to be on the location of the fighting or shelling which contributes to the overall legitimization of Ukrainian efforts to keep the their territorial integrity.

In conclusion

Collocation analysis, especially when based on statistical indicators that determine the strength of bonding between words, can be useful for linguistic, discursive and thematic analysis. It reveals both the routine formal language-specific patterns and the topical preoccupations in the body of texts. It can also help identify discursive strategies that are hard to notice with a “naked eye,” or confirm quantitatively some intuitive observations and claims made in the course of qualitative analysis.

Text by Katarzyna Molek-Kozakowska

References

Bingham, A. & Conboy, M. (2015) Tabloid Century: The Popular Press in Britain, 1896 to the present. Oxford: Peter Lang.

Kennedy, C.-R., Brookes, G. & Cherniaeva, A. (2024) Collocates: What are they and how can they be used to explore representation? Analysing Representation: A Corpus and Discourse Textbook. Heritage, F. & Taylor, C. (eds.), pp. 27-42. London: Routledge.

Molek-Kozakowska, K. (2013) Towards a pragma-linguistic framework for the study of sensationalism in news headlines. Discourse & Communication 7(2): 173–197.

Wilk, P. & Molek-Kozakowska, K. (2024) Constructing solidarity in discourse: A pragma-linguistic analysis of selected speeches by president Zelensky addressed to international community. Przegląd Wschodnioeuropejski 15(2).

Zelizer, B. (ed.) (2009) The Changing Faces of Journalism: Tabloidization, Technology and Truthiness. London: Routledge.