DisInfoResist is the name of the FORTHEM student-driven pilot study and intervention project devoted to building up resilience to disinformation on Russian-Ukrainian conflict among Polish teenagers. It took place in Opole in the spring semester of 2024 and was carried out by a group of University of Opole MA students of English Philology supervised by prof. Katarzyna Molek-Kozakowska in collaboration with CORECON and a local public comprehensive secondary school in Krapkowice, a town 30 km away from Opole.

Rationales and aims

The idea for the DisInfoResist project arose in early 2024, when the MA students just started taking their Academic Research module for their Academic Major in English Language and Communication Studies with prof. Katarzyna Molek-Kozakowska. This is where they got acquainted with various research orientations and approaches, including participatory methods, such as oral histories, citizen science, action research and co-creative interventions.

At the same time, a research group made of linguists and media and communication specialists at UO and ULBS launched the first joint actions within CORECON – the project exploring and comparing the corpus data on coverage of Russian-Ukrainian conflict in the Polish, Romanian and English-language media. As a result, some tasks and examples that MA students were exposed to in class were concerned with various representations of the war in the media, with special attention paid to the phenomena of fake news, disinformation, misinformation and malinformation.

To help the students to understand issues of disinformation better, ULBS expert Ecaterina Ilis, who is just concluding her PhD dissertation related to fake news, was invited to give a presentation on the theoretical concepts related to disinformation and to get the students acquainted with current research. In a follow-up practical workshop, UO students were able to learn about the mechanisms of disinformation campaigns through a simulation game and they were to analyze and assess fake war news from a variety of media sources. (More about that workshop here).

Ecaterina Ilis also identified a large data set of fake news related to the Ukrainian-Russian conflict in various languages and across various media, which was compiled by the experts and activists of VoxUkraine throughout 2022 and 2023. Their reports that list fake narratives and media sources that are pushing them are available online as “Propaganda Diary” and can be used for fact-checking.

All in all, DisInfoResist initiators have promised that the project and its interventions would enable young people to successfully spot and identify fake news about the Russian-Ukrainian conflict and develop a capacity of remaining resilient to disinformation. Resilience is understood here as the capacity to cope with stress, uncertainty and the sense of anxiety related to media exposure under traumatic circumstances, especially by developing coping mechanisms, be they cognitive, emotional or behavioral (Malecki et al., 2023).

Through a combination of research and intervention co-designed by UO and ULBS with the partner secondary school in Krapkowice, the project would seek to equip teenagers with the necessary awareness, analytic skills and media knowledge to critically evaluate information and resist the spread of disinformation (Guess et al., 2020).

Initial diagnosis: Teenagers’ narratives

As reliable diagnostic data related to the current situation are indispensable preconditions for a successful intervention, the first step has been to inquire how much Polish teenagers already know about the Russian-Ukrainian war, where they get that information from, and how they form their opinions and judgments about it. The aim was also to elicit information that would correctly diagnose the level of awareness (including language awareness) of various mechanics of disinformation and media manipulation.

The school teachers have been able to suggest the suitable ways to gain this kind of understanding and to identify the blind spots when it comes to exposure to and reception of war-related information by young people. The secondary school decided to select a cohort of first-graders (14-15-year-olds) as the best targets of DisInfoResist interventions, due to their being relatively vulnerable to media influence and their proneness to emotional volatility.

However, instead of a questionnaire or a structured interview, pupils were given 40 minutes of lesson time to express themselves in writing through a narrative that included the following six prompts asking them to share on:

- having any associations or images of the war starting or of any memorable media coverage (the aim here being to set the context for further information sharing);

- listing their preferred sources of information about the war and the way they customarily made use of them (the aim being to establish whether the pupils used the (social) media, the family/friends or the school as their dominant sources, and if news exposure was deliberate or occurred incidentally as a by-product of other activities, cf. Schäfer, 2023);

- identifying any changes to the way they approached media coverage since the war started, and if so how and why the change happened (the aim being to check if the pupils started taking any precautions against possible disinformation campaigns that might have been launched as part of hybrid warfare);

- naming any reactions and feelings they had in relation to the way the war developments were reported at the beginning and now (the aim being to spark reflection about how the information tended to make them feel and how emotions may have been driving their reactions, cf. Mousoulidou et al., 2024);

- reflecting on their attitudes with respect to the participants in the conflict, primarily Ukraine/Ukrainians and Russia/Russians (the aim being to elicit specific sentiments, attributions and representational patterns that pupils preferred, cf. Kubin and von Sikorski, 2021);

- expressing their expectations for the future (the aim being to bring closure to their reflections, or introduce additional nuances or aspects).

The narratives were anonymized; the pupils were allowed to write as much or as little as they wanted, but they were incentivized to be open about their opinions. The school also helped in co-creating, adapting and implementing the follow-up intervention.

Results and recommendations for the intervention

Over the course of the following weeks, the UO team read and processed almost a hundred of pupils’ narratives and coded and classified the data from narratives. Each narrative was analyzed by several students and the academic advisor, after which prominent keywords, patterns of expression and themes were identified. A list of dominant ways of expressing feelings, opinions and evaluations was compiled and recurrent content categories, themes or labels were calculated. The following are some of the major observations and follow-up recommendations:

1. Family and friends are popular sources of information since they are relatively easy to reach out to. However, these individuals have partial knowledge, subjective opinions and may not be as well informed about military details and political developments as experts. It is important for young people to have access to various sources of information, to be able to compare information, assess credibility and identify biases.

2. Some young people may have a tendency to deliberately avoid and block the inordinate amount of negative war-related information, which might be reasonable when their mental health is at stake, but ultimately having some orientation about the current issues is helpful is assessing credibility of sources and reliability of content.

3. Some young people have expressed a lot of concern about false information and are becoming more careful and scrupulous in examining news. It is important to note that various news media outlets are presenting contradictory information – either because they are reporting before all facts are established, or because they have a political agenda.

4. Widespread access to the internet causes that a lot of unverified information is publicized and propagated. It is recommended not to share or promote unverified information. Understanding the fact that disinformation is being circulated at all times, calls for more attentiveness and caution so that one does not fall victim to fake news scams.

5. The teens’ narratives also reveal high levels of stress related to the understanding of brutality and destruction brought by the war, as well as its possible long-term consequences for Europe. The sense of fear or threat is magnified by confusion and uncertainty in relation to disinformation, the lack of credibility and contradictory accounts, opinions or estimates. It is laudable that some young people continue to explore the issue of conflict to gain a better understanding of its causes and consequences and to prepare for actively realizing their citizenship. Hopes for peace and resolution are high because they allow young people to engage and promote positive values and constructive attitudes.

6. It can be observed then that political and military conflicts are accompanied by high emotional investments, polarized debates and hate speech. It is recommended that making subtle distinctions between refugees, migrants, citizens, military actors, political decision-makers and the nation state (in case of Ukraine/Ukrainians and Russia/Russians) allows for a more precise and just approach to the conflict. It is important to refrain from making sweeping generalizations, contribute to stereotyping and increasing polarization, as this makes any attempts at reconciliation harder.

Intervention: Workshops and simulation games

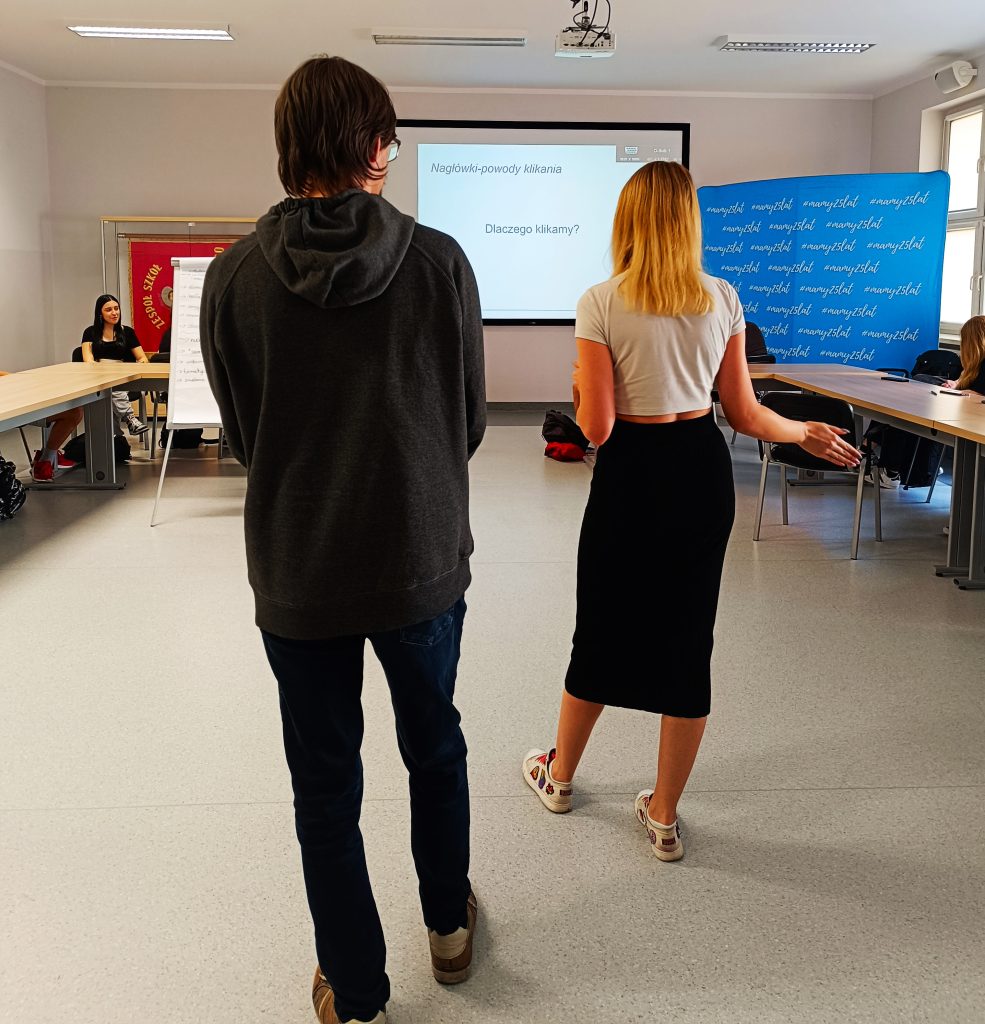

On the basis of the analysis of pupils’ narratives, it was possible for MA students and academics to assess what can be done to strengthen critical thinking, resilient media consumption and language awareness. The UO team approached the school teachers to co-create and calibrate some interventions, which were realized during a visit to the school on 6th June 2024. Those included:

- an overview of the teens’ typical patterns of media use and reception of Russian-Ukrainian conflict that were revealed in narratives with conclusions and recommendations developed on their basis (see above);

- a Kahoot quiz to check the level of teens’ ability to differentiate between fake news and true information related to the war, with subsequent discussion on the cases that were problematic;

- a workshop devoted to identifying the stylistic mechanisms through which media outlets may sensationalize the war coverage based on a CORECON corpus of authentic headlines from online versions of two Polish tabloids;

- an online role-playing game https://www.getbadnews.com/books/polish/ that shows how disinformation campaigns tend to be organized. The player is advised by a bot on the subsequent steps how to impersonate, misinform, and troll other media users – this reveals some of the tricks and traps that media users are likely to fall into when disinformation campaigns are coordinated by malicious agents;

- a tailor-made board game that teaches responsible media use by awarding points to players with dispositions to media literacy and eliminating players that chose to use media only for entertainment.

The narratives and the workshops in DisInfoResist revealed that while there is a relatively high awareness of headline manipulation for emotional stimulation, what the teens do not seem to be aware of is how the algorithmic design of information provision determines their exposure to certain information in the context of social media platforms and online portals. Young people need to be aware that by clicking cookies, accepting terms of use and allowing tracking or access to personal data they are training the algorithm to continue suggesting certain information that might be personalized or preferential and thus sealing off other important voices and contents. The aspect of digital algorithmic literacy needs to be strengthened if any future intervention is undertaken.

References

Guess, A. M., Lerner, M., Lyons, B., Montgomery, J. M., Nyhan, B., Reifler, J., Sircar, N. (2020). A digital media literacy intervention increases discernment between mainstream and false news in the United States and India. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 117 (27): 15536–15545.

Kubin, E., von Sikorski, C. (2021). The role of (social) media in political polarization: A systematic review. Annals of the International Communication Association, 45: 188–206.

Malecki, W. P., Bilandzic, H., Kowal, M., Sorokowski, P. (2023). Media experiences during the Ukraine war and their relationships with distress, anxiety and resilience. Journal of Psychiatric Research, 165: 273–281.

Mousoulidou, M., Taxitari, L., Christodoulou, A. (2024). Social media news headlines and their influence on well-being: Emotional states, emotion regulation, and resilience. European Journal of Investigation in Health, Psychology and Education, 14 (6): 1647–1665..

Schäfer, S. (2023). Incidental news exposure in a digital media environment: A scoping review of recent research. Annals of the International Communication Association, 47: 242–260. Katarzyna Molek-Kozakowska with inputs from student coordinator Julia Wnuk-Lipińska