On 8th April 2024 Ecaterina Ilis (ULBS) delivered a guest lecture “Researching fake news: Understanding the challenges” and a workshop to University of Opole MA students majoring in Language and Communication in the English Philology study program.

Given her long-standing interest in critical discourse analysis of mediated fake news in the context of COVID-19 pandemic, which is the basis of her PhD project developed at Lucian Blaga University in Sibiu, Ecaterina Ilis agreed to acquaint UO students with main approaches to fake-news research and the proposed ways of their identification and elimination.

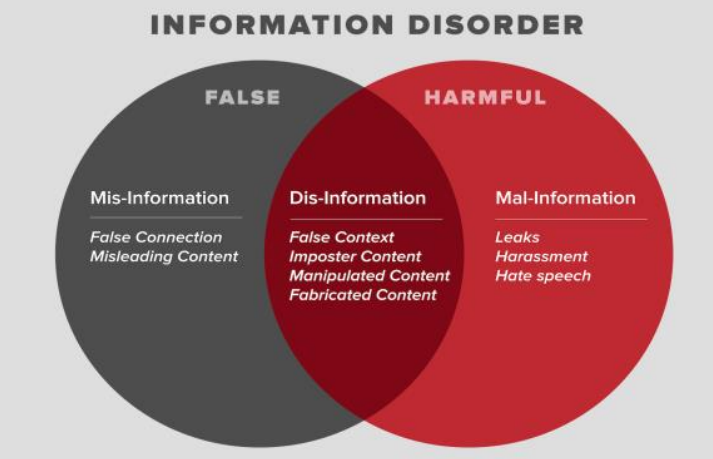

While the definitions of fake news proliferate and overlap with those of “disinformation,” “misinformation,” and “malinformation,” it is important to remember that all fake news items can be characterized by the following three traits: (1) a reduced level of facticity; (2) a goal of deceiving people; and (3) formats and language specific to the journalistic style.

Ecaterina’s lecture also explained how social media ecosystems have sparked an “infodemic” of fake news because of their low entry barriers, lack of editorial oversight, attention-grabbing headlines and in-built capacity for polarization and confirmation bias. The students taking part in the lecture admitted to being most interested in Ecaterina’s explanation of the psychological factors characterizing people who are susceptible to both replicating and producing fake news content. For example, people who experience the feelings of social alienation and skepticism, lack of agency and political marginalization and who distrust official media and institutions are likely to fall prey to fake narratives. Also, there is a budding, if still inconclusive, research on how personality traits and psychopathological inclinations make some people more likely to share and remember unconfirmed information.

What is of special importance is the role of cognitive factors, especially reliance on intuitive, less analytical reasoning, especially in cases of news items that coincide with preexisting beliefs and are congruent with generally held values, in making some individual prone to assimilating disinformation. This can be magnified in cases of repeated contact with the false information, as is the case with algorithmic echo-chambers on social platforms. After all, “a lie repeated a thousand times becomes the truth” in accordance with the illusion of truth effect created by repeated encounters with some ideas. This effect is likely to be induced for example by organized propaganda campaigns sometimes called a “firehose of falsehood”.

In the workshop part of the event, the students could play an online game “Bad News” in which they impersonated a malicious agent disseminating bad news and got to know about the tricks of the trade of being a manipulator. This allows the player to realize how often they may have fallen prey to engineered sensationalism around bad news, as well as hoaxes and trolling provocations.

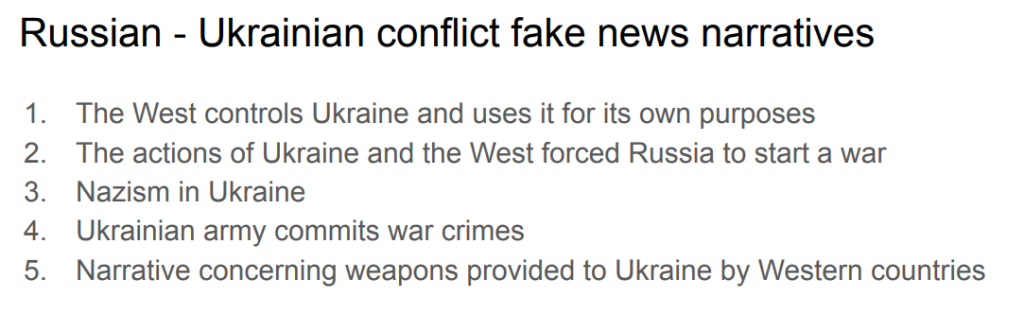

The students were then to work on identifying fake news in conflict zones based on a typology of propaganda (Wardle and Derkashan, 2017) and the ways the false narratives are used. Given 5 selected false news narratives identified by “Propaganda Diary” project by VoxUkraine, students were asked to discuss the meaning, purpose and implications of each of them.

Finally, students helped to produce a list of key discursive strategies that are employed by propagandists to more effectively propagate false narratives. These include:

- (de)legitimization through moral and legal rhetoric,

- (false) historical contextualization,

- (imputed) moral equivalence in victimhood,

- security threat construction,

- emotional manipulation,

- simplification and generalization of complex issues,

- false dichotomies in “Us vs. Them” framing.

Ecaterina highlighted the importance of applying theoretical concepts practically, stressing the critical need for future professionals to be adept at identifying and understanding misinformation: ”While preparing for the workshop, I thought about bridging theory and practice and helping to raise awareness about the complex nature of fake news, its impact, and the importance of critical media literacy. I considered the necessity of engaging the students actively in understanding not just the definitions and characteristics of fake news but also the psychological and social dynamics that contribute to its spread. This has become especially significant as we witness the scale at which misinformation has been weaponized in the Russian-Ukrainian conflict, influencing public opinion and international relations. The goal was to inspire a proactive approach in students, equipping them with analytical tools to challenge and navigate the misinformation landscape effectively.”

Text by Katarzyna Molek-Kozakowska and Ecaterina Ilis

Useful materials

- Goreis, A., and M. Voracek. “A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Psychological Research on Conspiracy Beliefs: Field Characteristics, Measurement Instruments, and Associations With Personality Traits.” Frontiers in Psychology, vol. 10, no. 2019, https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fpsyg.2019.00205

- Lazer, D.M.J., et al. “The science of fake news.” Science, vol. 359, no. 6380, 2018, pp. 1094-1096, 10.1126/science.aao2998

- Pennycook, G., and D. G. Rand. “The psychology of fake news.” Trends in Cognitive Sciences, vol. 25, no. 5, 2021, pp. 388–402, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tics.2021.02.007.

- Vosoughi, S., et al. “The spread of true and false news online.” Science, vol. 359, no. 6380, 2018, pp. 1146–1151, https://www.science.org/doi/10.1126/science.aap9559

- Wardle, C., and H. Derakhshan. “Information Disorder: Toward an interdisciplinary framework for research and policy making.” Council of Europe report DGI 2017 09.

- Yale University’s Information Society Project’s ‘Fighting Fake News’ Workshop https://law.yale.edu/system/files/area/center/isp/documents/fighting_fake_news_- _workshop_report.pdf

Ecaterina’s entire presentation is available below: